Stories of Russian Crown jewels’ sales, thefts, smuggling and hoarding – covered in the press – date from May 1917, just two months after Tsar Nicholas II’ abdication. Marguerite Cunliffe-Owen, who wrote as La Marquise de Fontenoy, referred to the Provisional Government such that if it had its way, ‘…some of the very finest jewels in the world will shortly be placed on the market, for its leaders are anxious to convert into cash and, above all, get rid of the magnificent crown jewels…to be able to convince people at home and abroad that there will be no restoration of the monarchy in Russia’. It is generally agreed that the first concerted attempt to sell items previously owned by the Romanovs took place in May 1918 when two individuals tried to smuggle highly valuable imperial jewels into New York, their efforts were thwarted. In 1919 the founding congress of the Communist International took place in Moscow and soon afterwards agents of the International were regularly exporting gold jewellery and precious stones from Moscow, however, there was very little control over their activities and many items were simply stolen rather than helping to patch up the economic fallout from the revolution.

Spotlight on an impressive diamond ornament and its imperial legacy | Part II

In February 1920, against the backdrop of a fragile economy combined with the need to bring order to the management of the Bolsheviks’ high-profile legacy a decree established the state institution of the Gokhran. It was to be responsible for the purchase, storage, sale and use of precious metals, precious stones, jewellery, rocks, and minerals. In the immediate years following the revolution the Gokhran amassed jewellery previously belonging to the Romanovs, the Kremlin Armoury and the Russian Orthodox Church as well as valuables taken from private collections. By law, all stored, managed, altered or registered valuables made of gold, platinum, precious stones and pearls had to be delivered to the Gokhran, within three months. The following year, the Riga Peace Treaty withdrew Ukraine and Belarus from Russia to Poland, with Russia pledging to pay Poland 30m gold rubles, within the year, in lieu of assets and treasures Russia had removed from Poland.

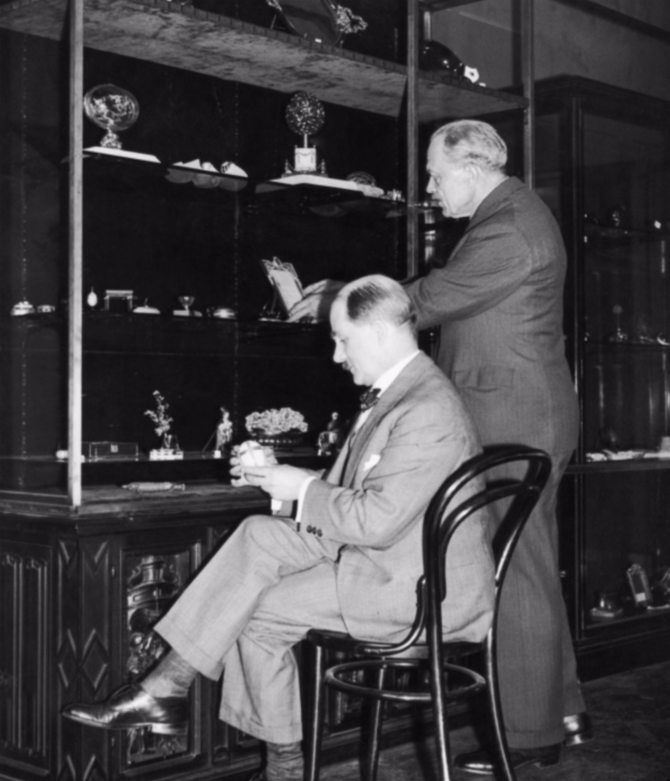

Tsar Peter I’s 1719 decree had forbidden the giving, changing or selling of items in the Diamond Fund and over a period of 200 years the Treasury had only ever been replenished, but the Bolsheviks had no intention of respecting these instructions. The route to realising hard currency from the jewels was shaky, but finally the decision was made to sell the jewels abroad, and therefore an inventory and a valuation were required. Unfortunately, the Gokhran no longer had specialists with the necessary skills to run such an important project – in late 1921 a number of appraisers had been imprisoned for theft, and three experts were shot such was the serious nature of their pilfering. Alexander Krasnoshchekov, Deputy People’s Commissar for Finance, appointed by Lenin in December 1921, rounded up former Fabergé jewellers to handle the task, amongst them, Georgi Utkin, Carl Bock, A F Kotler and Agathon Fabergé, who by 1920, aged forty-four, was grey-haired and described as ‘old’. Understandably, he was a broken man, he had lost his business and home, and had been branded a ‘bourgeois counter revolutionary’ for which he served a year in a concentration camp where on three occasions he had been taken out to be shot.

Two commissions took charge of the jewels, work took place at the Kremlin Armoury, where the inventory of the jewels was created, and at the Gokhran, located within the Loan Treasury building, the valuation was generated. Ironically construction work on the Treasury building had commenced in 1913, to tie in with the Tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty. The architects, Vladimir Pokrovsky and Bogdan Nilus were personally selected by Nicholas II and the building was finished just a year before the revolutionary acts of 1917.

Alexander Fersman (1883-1945), a key member of the commission, later recalled, ‘…we walked through the frozen rooms of the Armoury…They brought boxes…among them a heavy iron chest, tied, with large wax seals…An experienced locksmith easily, without a key, opened an unpretentious, very bad lock. Inside there were jewels of the former Russian Court, each one hastily wrapped in tissue paper…we took out one sparkling gem after another…’. Fersman, a geochemist and mineralogist, had been appointed a full member of the USSR Academy of Sciences in 1919, his early research had focused on the minerals found in Crimea and as a post graduate he had studied natural diamond crystals in Germany. In the course of his career he discovered several mineral deposits, wrote many books and published over 1,500 articles – the writer Alexei Tolstoy called him a ‘poet of the stone’.

One of the Fabergé jewellers, Kotler, advised the authorities that if a buyer could be found for the jewels a sum close to 500m gold rubles cold be realised, and in addition the coronation regalia was possibly worth several million rubles. The regime was concerned about the resultant negative publicity should the Romanov jewels be sold as a collection and gave consideration to the discreet sale of items on an individual basis. By mid-May 1922 the valuation work had progressed significantly, and at great speed, and ‘items from the former House of Romanov’ were categorised according to three criteria: ‘All the jewels of great value and historic fame’; ‘Specimens of minor interest’ and ‘Old fashioned jewels, loose stones and quaint jewelled trinkets’. Alexei Rykov (1881-1938), the recently appointed Deputy Chairman of the Council of Labour and Defence, under Lenin, questioned Fabergé and Fersman on the coronation items: could their value be achieved on the open market? Their opinion was that it was possible, but that there should be no rush to sell. The Bolsheviks were not listening, they were under immense pressure to secure foreign currency. From 1922, emeralds, pearls and diamonds previously owned by the Romanovs were sold in Amsterdam, Paris and London. As for the debt to Poland, in a ceremony held in Warsaw in March 2023 the original Treaty of Riga was formally installed in the Archives of Modern Records. At the event, Deputy Minister Arkadiusz Mularczyk noted in his speech that the Treaty of 1921 had not only mapped Poland’s eastern border but had committed Russia to pay 30m rubles to Poland – a sum which was still outstanding.