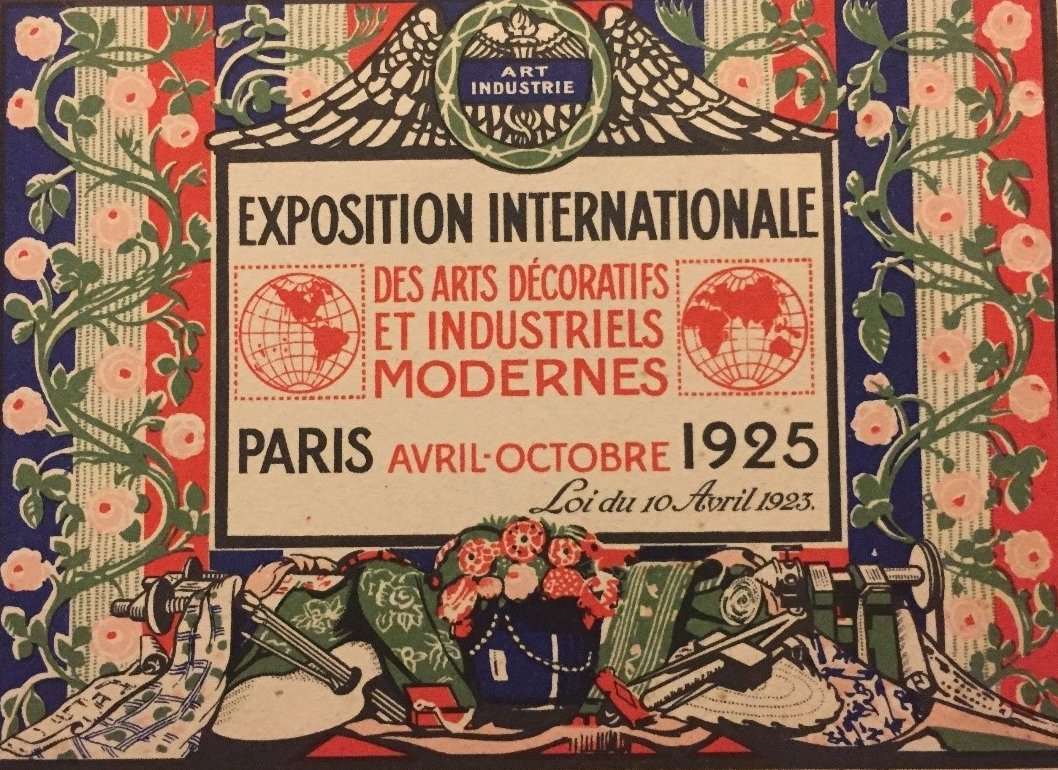

The Jazz Age, a term coined by Scott Fitzgerald was a twilight epoch between the wars of innovation and excess. Fitzgerald’s iconic novel The Great Gatsby has come to represent the era as one of cocktail parties, flappers and prohibition. The aesthetics of the era had evolved from many diverse influences: Cubism, Modernism, Futurism, Industrialism, Brutalism and Orientalism and was articulated artistically through the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925.

The journey from Art Moderne to Art Deco

Justin Roberts, Jewellery Specialist, Historian and Lecturer, takes us on a glittering tour of this most stylish of art movements

The International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris, 1925, showcased the aesthetic's of Art Deco and gave the movement its name

Lacquer and silver cigarette case and a platinum and diamond clip, Raymond Templier, circa 1930

The Exposition was to symbolise the movement and later gave it its name, Art Deco, crafted by the historian Bevis Hillier in 1966. Art Deco was formed of three defining tenets: bold geometric shapes, rich colours and lavish ornament, whether architecture or jewels, true Art Deco was to encapsulate all three. At the time these developments would have been known as Art Modern – the new modern style sweeping throughout the globe. In Paris, these new ideas were brought together and were mixed with the avant-garde – Templier, Sandoz, Fouquet and Dunard with their striking modernist designs exhibited alongside the fabulous Eastern inspired jewels of Cartier. Notably, a fabulous shoulder ornament made for the exhibition was embellished with carved Mughal emeralds; the jewel’s life was sadly short lived, as it failed to find a buyer and was dismantled in 1926, re-purposed into more commercial jewels the few surviving elements give us a tantalising glimpse of this once magnificent jewel.

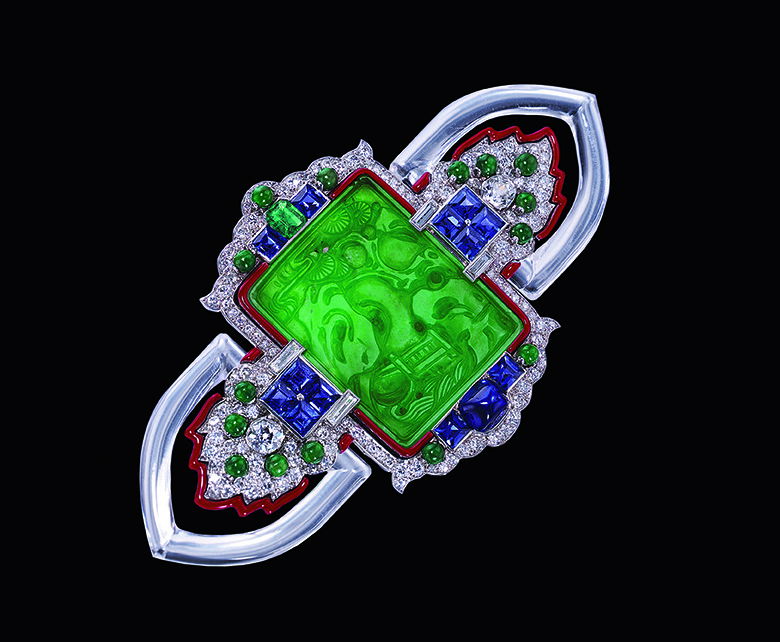

Jadeite, enamel, gem-set and diamond brooch, Cartier, circa 1927

Raymond Templier, embraced a style of enamel and diamonds, the use of geometry and colour taking precedence over stones. Gerard Sandoz embraced materials for the effect over the intrinsic value – he worked in silver, lacquer and enamel – a pioneer in modern jewellery design he was to close his firm in 1931 to devote his attention to painting and cinema. Jean Dunard pioneered the use of egg shell lacquer, broken egg shells forming a mosaic in white, he was even to design a smoking room for the 1925 Exposition, such was the diversity and range of the new goldsmiths of the age.

In some instances, jewellery designers would showcase their creations alongside striking modernist art, the jewels becoming miniature examples of Cubist art, as with Templier who exhibited his Cubist inspired cigarette cases against a backdrop of art by Fernand Léger. Jean Després, another innovative goldsmith at the time, was inspired and influenced by his work as an aviation engineer during the First World War, he adopted an Industrial look, where the machine was embraced and displayed rather than concealed. Jean Fouquet, the son of George, took the firm in a completely new direction with his pared back modern designs demonstrating the sway of the Italian Futurist, Antonio Sant’ Elia, along with Orientalism showcased in his iconic Oriental mask brooch of jade and diamonds which perfectly combines the three Art Deco creeds of shape, colour and ornament.

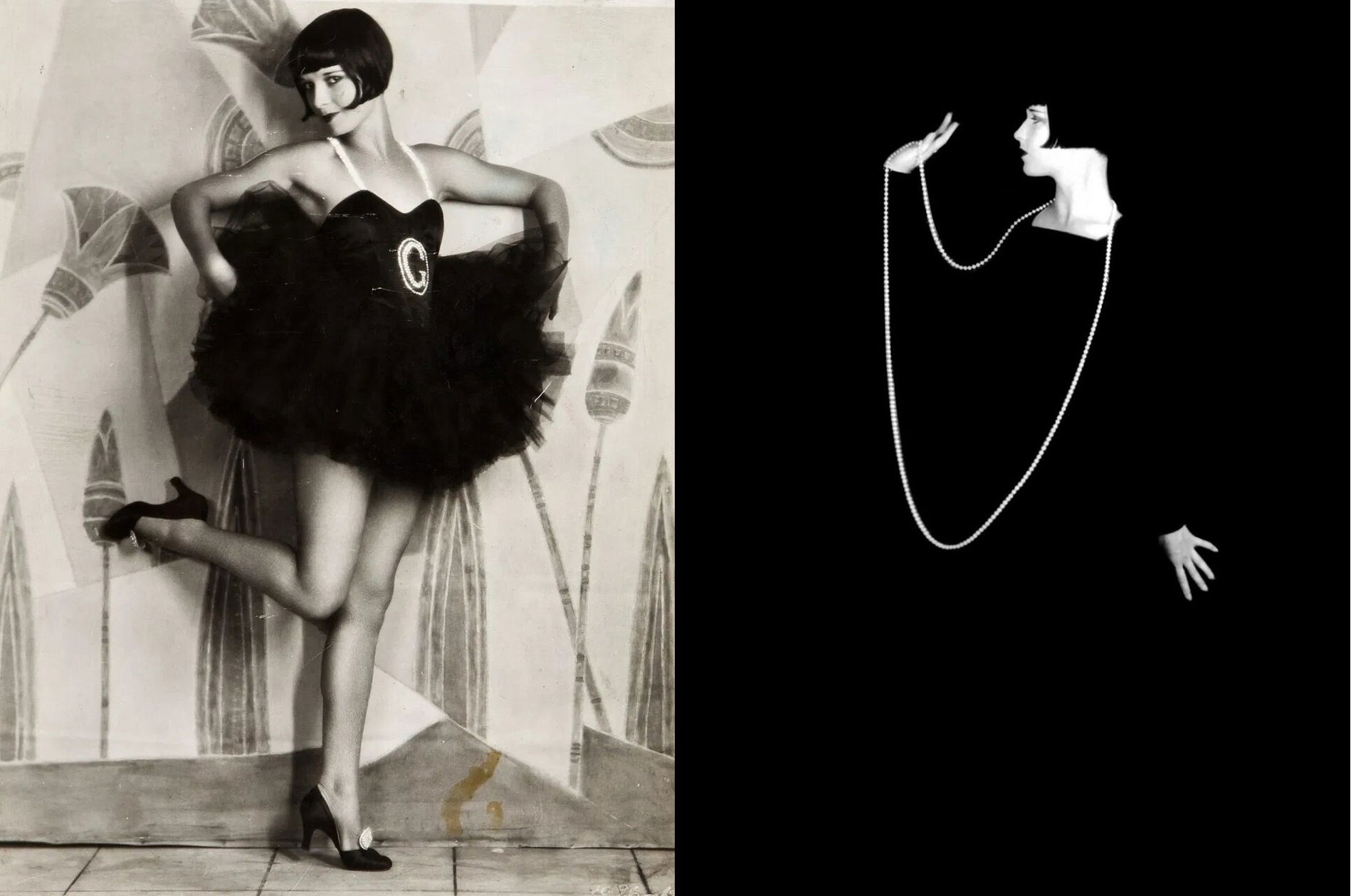

Louise Brooks, actress and dancer, shot by Eugene Robert Richee, 1929 and 1928; with her bob hairstyle and flapper attire Brooks epitomised the Jazz Age

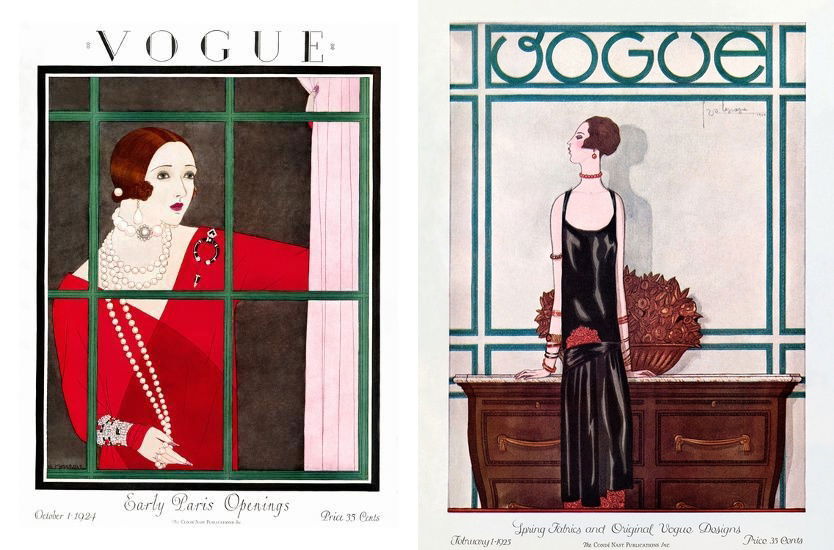

Fritz Lang’s 1927 movie Metropolis is a cinematic representation of Art Modern/Art Deco, illustrating every influence of the movement, from its modern city scape to the wonderfully decadent oriental inspired night club Yoshiwara. It was a time of decadence – speakeasies and illegal drinking, smoking and partying. The Kit Kat, Eldorado, Cotton and Stork clubs were real clubs with names just as exotic as the fictional Yoshiwara. Bedecked in jewels the fashionable flapper would smoke oriental cigarettes, drink cocktails and dance the Charleston. Hair cut short to a bob and skirts hiked, the female silhouette became defined by a more linear form. Long beaded necklaces to complement the beaded dresses, elongated earrings to enhance the neck and shoulders and wrists stacked with gem-set and diamond bracelets in a panorama of geometric forms. Josephine Baker with her Danse Savage and Marlene Dietrich in the Blue Angel pushed the boundaries of excess and liberty.

Diamond double-clip brooch, Cartier, 1930s

“Orange and black, blue and green, red and yellow were popular colour combinations favoured for their dramatic, audacious contrasts and conspicuous display – the Jazz Age was anything but understated. Presented to us in black and white photographs, the reality was in fact vibrant and bold”.

Vogue, October 1924 and February 1925

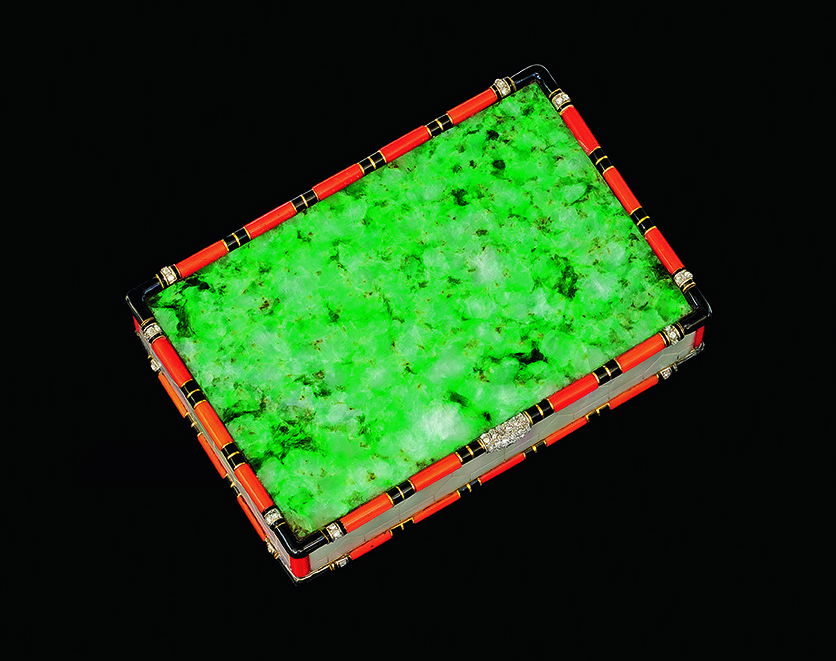

The senses were overloaded with a surfeit of ornament, and combining the new with the old many jewellers happily re-fashioned old elements into the new modern Art Deco idiom. From antique Chinese jades transformed into watches, brooches and earrings, to Kangxi lacquer trays converted into vanity cases and cigarette lighters. Cartier was particularly adept at ingenious transformations and the imaginative utilisation of ancient and antique works of art from India, China and Egypt.

The dazzling self-indulgence of the Jazz Age was to come to an abrupt halt with the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Transferred to the silver screen, cinema was to become the predominant showcase for Art Deco, an escapism from the Depression and growing political unrest of the 1930s. Art Deco evolved into a more monochromatic palette with stronger and bolder geometric lines. Diamonds, onyx and rock crystal predominated and were perfectly suited to the new close up of the screen and Hollywood allure and they embraced Art Deco with its portrayal of a glamorous lifestyle of freedom and fun, showcased from the new Odeon picture palaces.

Jade, coral, mother-of-pearl, enamel and diamond compact, Cartier, circa 1925

Wearing the latest modern jewellery, Gloria Swanson was pictured in a film still from the 1933 movie, A Perfect Understanding, wearing her own pair of Cartier rock crystal and diamond bangles. The bangles she was to ironically wear again in her famous comeback movie of 1950, Sunset Boulevard, where she portrayed a reclusive 1920s’ film star living her glamorous 1920s’ lifestyle from the faded opulence of her Hollywood mansion.

By the close of the 1930s and the advent of the Second World War true Art Deco had run its course and was to be slowly replaced by the ribbons and scrolls of the New Look of the post-War 1950s.