The show focuses on the importance of the firm’s London branch which opened in 1903, its Edwardian clientele and Fabergé’s creative triumphs in Britain. Comprising over 200 objects, the exhibition considers the Anglo-Russian relationship and demonstrates that works by Fabergé were as popular in Britain as they were in Russia. Huge success at the 1900 Paris Exposition had indicated that Fabergé would have a captive audience outside Russia, and London was selected given its status as the financial capital of the world, a luxury retail destination able to draw in an international clientele, and importantly, King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra were already Fabergé collectors, so royal patronage in London was virtually guaranteed.

Understanding Jewellery visits Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution | V&A Museum, London

We were lucky to have an early viewing of the V&A’s glittering new exhibition, Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution.

From many wonderful pieces, three exhibits caught our eye and prompted us to find out more about their history and the contexts in which they were created.

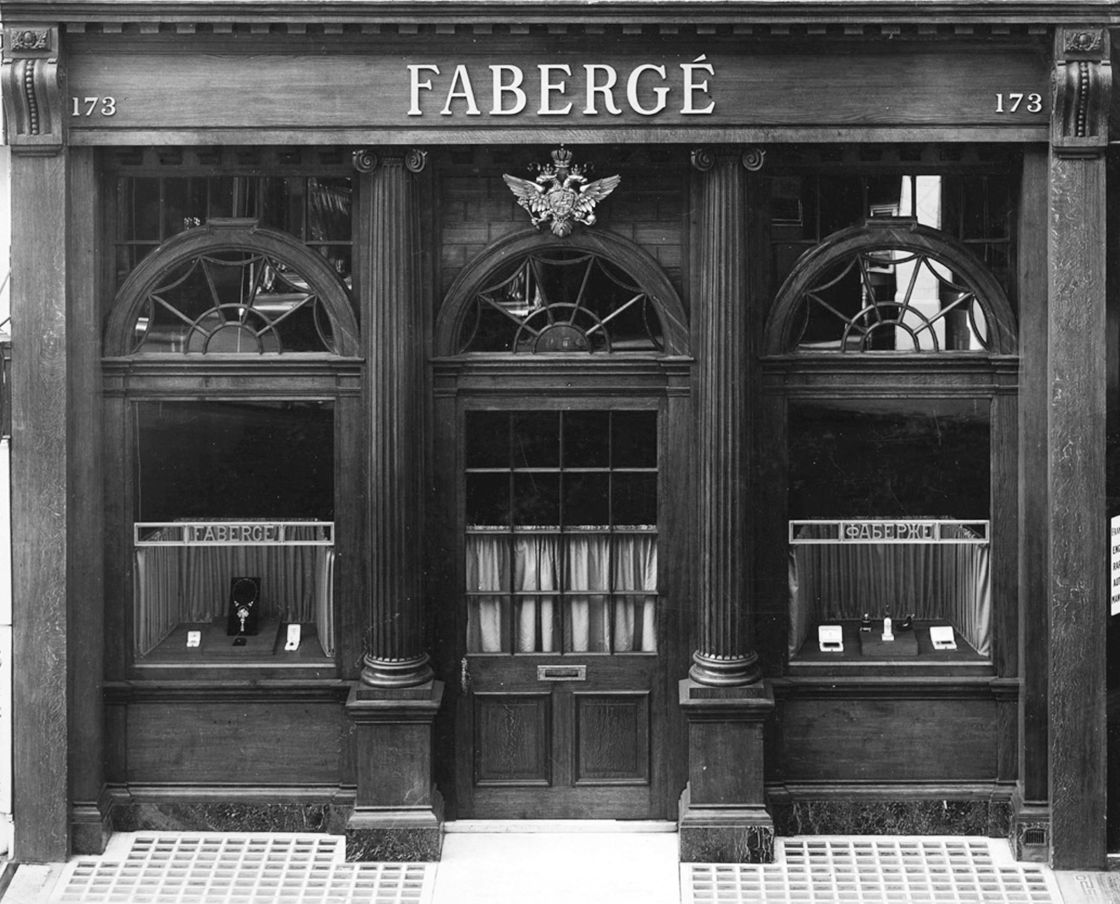

Fabergé’, London , at 173 New Bond Street; the branch opened in 1903 and closed in 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution

Imperial presentation box by Fabergé’, nephrite, coloured gold, diamonds, ivory

Chief Workmaster: Henrik Wigström, St. Petersburg, 1904

Private collection, image courtesy of Wartski, London

We start with this Imperial presentation box from 1904. In nephrite and coloured gold, decorated with diamonds and ivory and featuring a portrait miniature of Tsar Nicholas II, it was created in St. Petersburg under the supervision of Chief Workmaster, Henrik Wigström (1862-1923) – he had assumed the role in 1903 following the death of Michael Perchin, Fabergé’s innovative workmaster whose output covered a huge range of styles. From the reign of Peter the Great, sovereigns presented gifts embellished with their images. The practice of awarding jewelled snuff boxes gathered pace during the reigns of Empresses Elizabeth and Catherine the Great, when snuff taking grew into an elaborate social ritual and luxurious snuff boxes became an art form – the custom was to continue long after snuff went out of fashion.

Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, and their children, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia and Alexei

The most frequently awarded portrait gift during the reign of Nicholas II was the jewelled snuff box, fifty four in total, (only nineteen of these were created by Fabergé) bestowed upon both prominent Russian nationals (twenty snuff boxes) and foreign dignitaries (thirty four snuff boxes). The giving of a snuff box was not down to personal preferences or generosity, but rather in the interest of the Empire. Awards to Russian nationals created bonds of loyalty, between the ruler and those who served him, whereas those given to foreign dignitaries were either for purely diplomatic reasons or to recognise a special occasion linked to the Imperial family. For this second group of recipients, the intrinsic value of the piece is a clear indicator of the importance of the relations between Russia and the recipient’s realm. Fabergé became the Court Jeweller in 1884, and the Imperial Cabinet was responsible for purchasing presentation boxes, which were supplied with an empty diamond cartouche, so that either the diamond cypher or the Tsar’s portrait could be mounted.

An important aquamarine and diamond tiara by Fabergé, aquamarine, diamond, silver, gold

Workmaster Albert Holmström, St. Petersburg, circa 1904

Photography courtesy of HMNS | Photographer: Mike Rathke

From the same year, 1904, this aquamarine and diamond tiara, (workmaster, Albert Holmström) in silver and gold, was created to a symbolic design known as ‘Triumph of Love’. Composed of nine graduated pear-shaped aquamarines, old-, cushion- and rose-cut diamonds, it features forget-me-not flowers tied with bows signifying true and eternal love, pierced by arrows representing Cupid – the god of attraction and affection. Unsurprisingly, this highly romantic jewel was a wedding gift, from Frederick Francis IV, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1882-1945) for his bride, Princess Alexandra of Hanover and Cumberland (1882-1963). The Grand Duke’s mother, Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna of Russia was an enthusiastic Fabergé admirer and collector and she encouraged her son to source his nuptial gift from the Fabergé atelier in St. Petersburg.

Princess Alexandra of Hanover and Cumberland (1882-1963) wearing her aquamarine and diamond tiara shortly after her wedding in 1904

Interestingly, records show the exchanges between the Grand Ducal Cabinet of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Eugène Fabergé (the son of Carl Fabergé), but given the protracted nature of the discourse on the design and pricing of the tiara, the piece was not ready in time for the wedding held on 7 June 1904. Just two weeks before the wedding Fabergé had written to the Ducal Cabinet advising that he had not yet received confirmation to proceed with the tiara. Instead the bride wore the Hanoverian family tiara from the wedding of George III and Queen Charlotte. A month later Princess Alexandra was spotted wearing her new aquamarine tiara at a court ball, matched with a pink silk dress and pearl necklaces.

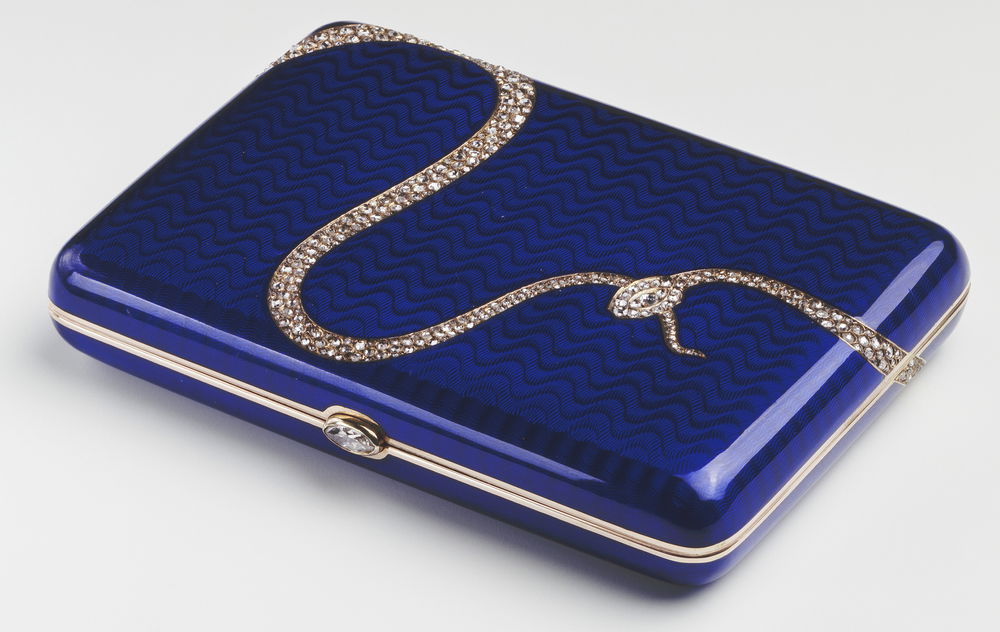

Cigarette case, Fabergé.two colour gold, guilloché enamel, diamonds, 1908

Royal Collection Trust | © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021

Another love story is marked by our third piece, a stunning Art Nouveau cigarette case in gold, dark blue moiré guilloché enamel and diamonds, dating from around 1905 and created in Fabergé’s Moscow workshops. It was given to King Edward VII by Alice Keppel, his mistress, in 1908 and it celebrates her undying love for the monarch. A diamond snake encircles the box and bites its tail, symbolising never-ending devotion and the use of diamonds is doubly symbolic, their durability indicating constancy. Recognising the significance of the case Queen Alexandra returned it to Mrs Keppel in 1910 on the death of King Edward. However, in 1936 it came full circle when Mrs Keppel gave the case to Queen Mary so ensuring it remained in royal ownership.

King Edward VIII at a country house party, West Dean Park, Chichester; Alice Keppel is standing directly behind the King

Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution at the V&A Museum, London is open until 8th May 2022 | Find out more here