The demand for armaments in the 1940s resulted in restricted supplies of platinum and the alloys of nickel, copper and zinc – used to create white gold – for anything other than the war effort. This left yellow gold and silver as the principal materials for jewellery manufacturers. 14 carat gold in particular was favoured as its lower purity made it affordable, and its copper-rich alloys were to create the distinctive pinkish tones which became emblematic of the jewellery of the era.

Retro jewels - created for the challenging 1940s and inspired by Art Deco designs

Justin Roberts, Jewellery Specialist, Historian and Lecturer, discusses how post-war jewellery design evolved out of the late Art Modern or Art Deco style and was moulded by the dramatic world events of the 1940s.

The use of two coloured gold, large flower head motifs and repoussé work are all typical of the era

The design of this clip includes several popular motifs of the period. namely scrolls, ribbons and interlocking rings, all treated in the bold, three-dimensional manner so fashionable in the 1940s

Moving away from the rigid, geometric forms of the 1930s the jewels of the 1940s and 1950s evolved into three-dimensional, often sculptural, fluid creations. The war time restrictions also limited the supply of gemstones from Asia, resulting in design taking precedence over intrinsic value. Precious stones, when used, were either re-purposed from earlier jewels or small in size and often featured as mere accents. Man-made synthetic gemstones, notably rubies, became a popular option, as natural gems could no longer be sourced from the Far East.

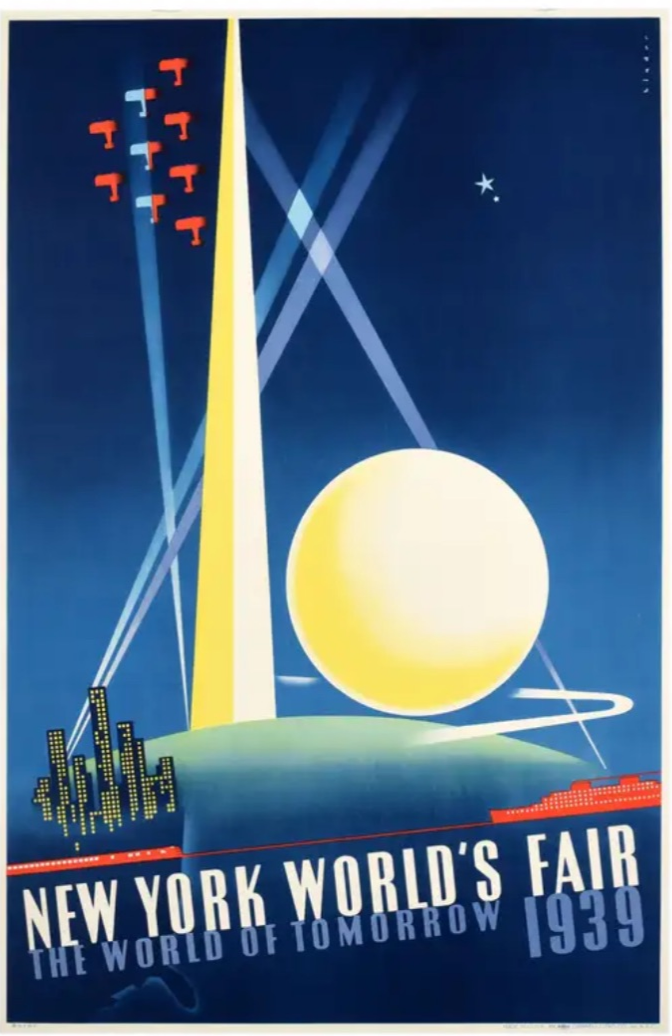

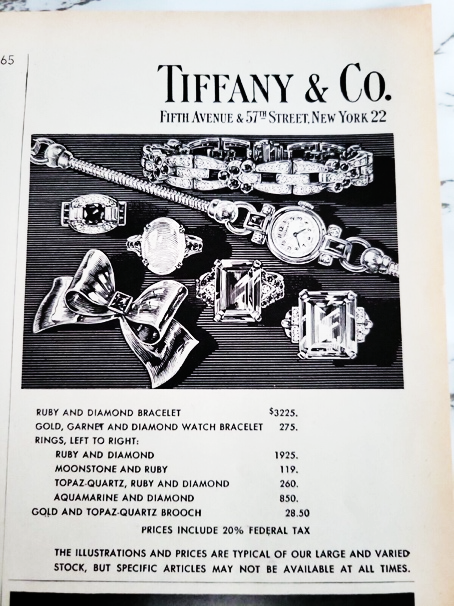

Participation at New York’s World’s Fair was a defining and important moment for two major jewellery houses: Van Cleef & Arpels and Tiffany & Co. Both firms exhibited creations in the new evolutionary take on Art Deco, and the style was swiftly embraced and copied by other manufacturers.

The new emphasis was now on bold asymmetrical designs emblazoned with brightly coloured gems. Given the economic circumstances, lesser value stones, such as aquamarines, citrines, amethysts, garnets and even moonstones, featured more prominently, while more the more precious gems, diamonds, sapphires, rubies and emeralds played a minor role.

Van Cleef & Arpels excelled in the creation of flamboyant floral spray brooches, rendered in rose and yellow gold and set with pastel-coloured gems. With their bold and fluid forms they embraced the new style and provided the perfect response to the less formal jewels worn at this time of pared down entertaining.

The naturalistic gold sprays of flowers set with tiny rubies and sapphires seen in the Hawaii collection, introduced in the 1930s, became increasingly fashionable in the 1940s, while the Capillaire and Pelouse designs, further variations on the naturalistic theme with their fine ramifications of gold wires and beaded work embellished with flower clusters, remained popular into the following decade.

The jewel was highly admired and frequently copied

In shifting economic conditions and the reduced social scene of the period day-time jewels came to the fore over the more formal diamond creations of the 1930s.

Van Cleef & Arpels Cadenas bracelet-watch, modelled on a padlock and first seen in the 1930s, became widely fashionable with its double strands of tubular linking and the ingenious concealed dial only visible to the wearer.

First created in 1935, the bracelet-watch allows the wearer to discretely check the time as the dial is mounted at an angle onto the jewel and can only be seen by the wearer

The Ludo Hexagon bracelet, created in 1935 and named in honour of Louis Arpels’ nickname, Ludo, became another favourite of the period with its wide band of yellow gold hexagonal links, each set with a small diamond in a star motif.

The Ludo was originally created in 1934 as an articulated band of rectangular links arranged in a brick pattern. In 1935 Van Cleef & Arpels introduced the Ludo Hexagon model where hexagonal links were arranged in a honeycomb pattern and star-set with gems

Gold brooches and earclips of scroll and swirl design, such as the Tourbillon range created in 1948, featured prominently in Van Cleef & Arpels’ production of the 1940s and 1950s. Stamped from thin sheets of gold which created the illusion of bulk without the accompanying volume whilst also respecting the economic constraints of the decade, these jewels were bold and elegant fashion statements.

The new jewellery style was ardently embraced in America where in the Post-Depression era the informality of the cocktail party became the fashionable form of social entertaining.

Tiffany & Co. were to lead the way in these developments. The jewels they exhibited at the World’s Fair featured large faceted aquamarines and cabochon moonstones framed by small sapphires and diamonds set into gold ribbons and scroll motifs stamped out of thin gold sheets. They were original, bold and relatively inexpensive fashion statements which were to become synonymous with the new ‘cocktail jewellery’. Large step-cut citrines in a variety of hues of yellow and brown were seen in American jewellery at this time. Citrine quartz was affordable and could be obtained relatively easily from South America during the war, whereas the supply of precious gemstones from Asia and Africa had dried up. Typically set within furled ribbons of copper-coloured gold, citrines were often surrounded or highlighted with small rubies or sapphires. These large, colourful and dramatic jewels came to represent a key component of American style in the 1940s.

The glamour of the 1950s made this style of jewellery, so closely associated with war-time restrictions and the ensuing post-war austerity, unfashionable and therefore redundant. Its popularity was however to be revived in the 1980s when ‘cocktail jewellery’ became appreciated anew for its bold designs and wearability. The large scale, sculptural forms and bold colouring of these jewels perfectly complemented the sharp lines, exaggerated shoulders and big, bouffant hairstyles of the decade. Furthermore, the jewels had survived in large quantities as the relatively low instrinsic value of lightweight 14ct gold and semi-precious stones protected them from being dismantled and re-fashioned. In the 1980s their abundance presented an affordable and wearable variant of Art Deco jewellery.

A new word, ‘Retro’ – short for retrograde – was introduced to categorise and identify the design of jewels created in the 1940s. The distinctive style was recognised as an evolution of Art Deco, drawing on inspiration from the 1930s, but shaped by the economic, social and cultural conditions of the World War II era and its aftermath. Retro was never truly a new style in its own right, but rather an imaginative re-working of what had gone before.