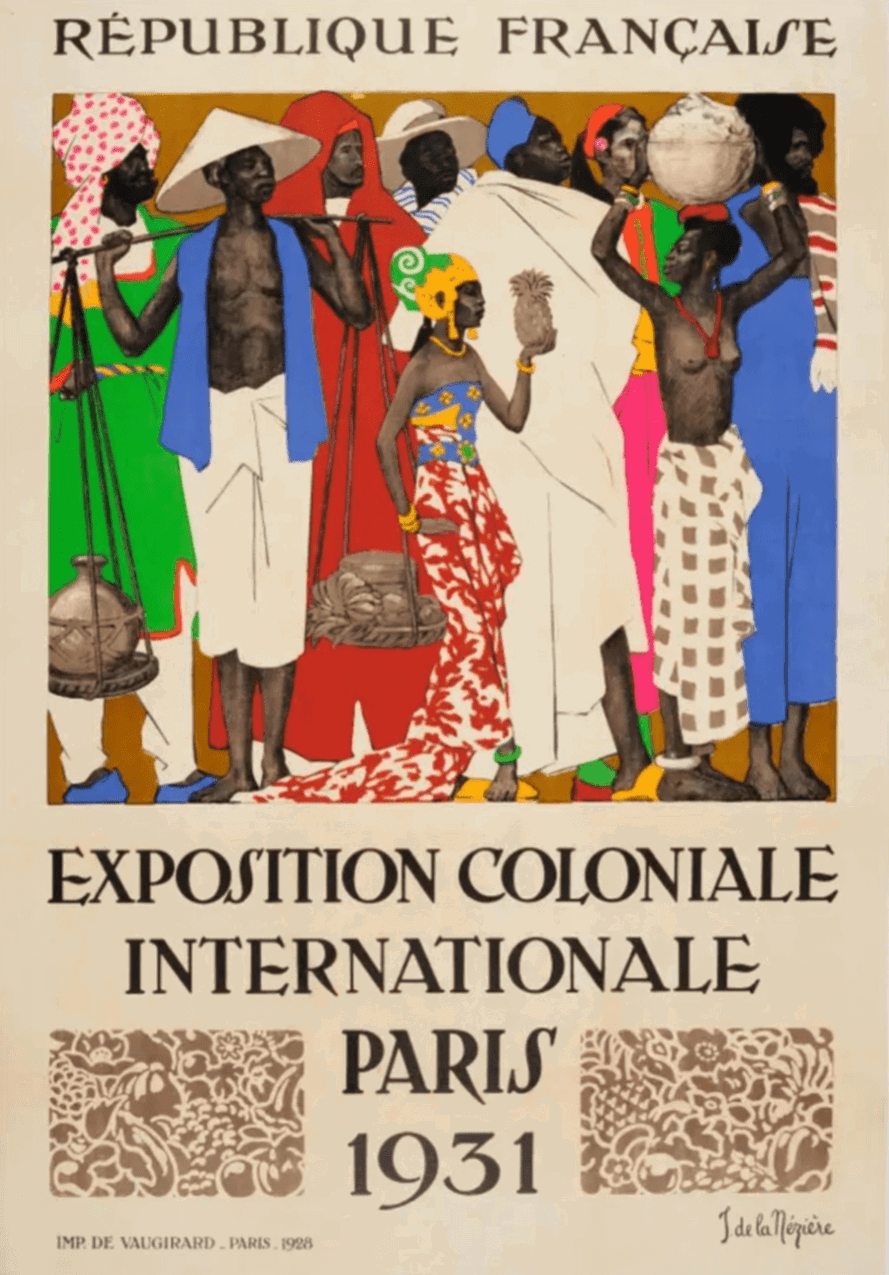

Exposition Coloniale Internationale de Paris, the Paris Colonial exhibition of 1931, was a six-month long event devised to showcase the diverse cultures and arts of France’s colonial territories. Similar in format to the British Empire Exhibition held in London in 1924, it was the culmination of 25 years of planning that started in 1906, the aim being the promotion of the notion of France as a Republic and an Empire.

The pivotal Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931 and its role in jewellery design

Justin Roberts, Jewellery Specialist, Historian and Lecturer, discusses this seminal exhibition and the ensuing influence it exerted in jewellery design.

The objective of the exhibition was twofold: to showcase the French Empire in a positive light in order to counter both German and Soviet criticism of France as an exploiter of its colonies, whilst endorsing France as associating with rather than merely assimilating these countries. The exhibition was held on the eastern outskirts of Paris in the Bois de Vincennes, the core of which was a Hall designed specifically for the Exposition by the French architects Albert Laprade, Léon Jaussely and Léon Brazin, the site occupied some 500 acres of parkland. In all, 26 territories of the French Empire took part, and other countries contributed, namely, the United States – with displays from Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, The Virgin Islands and Samoa – The Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Japan, Portugal, and Denmark, which curiously presented dioramas of Greenland’s stark, bleak landscapes. The group of international participants helped to give the Exposition the air of a World Trade Fair.

The arts and culture of French colonial Africa became the focus of the exhibition, and this in turn re-ignited interest in much of Africa’s past and present creative output. African art played a key role in the myriad of influences on the new Art Moderne movement, which was instigated at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, however the Paris Colonial Exhibition placed it centre stage. Elaborate screens and panels, lacquered in bronze and silver depicting exotic dancing figures in tribal costumes fired a fascination with lives and lifestyles which appeared unsullied by the rigours of the modern industrial age. Africa was not to be the only source of inspiration, the Island Kingdoms of the Pacific, such as the Hawaiian Islands, and The Philippines, also provided artistic motifs.

A monumental stone sculpture by Alfred Janniot (1889-1969) was specially commissioned to embellish the Palais de la Porte Dorée which was constructed for the Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931. It featured scenes from various French colonies and included a frieze titled Tahiti, an example of how the new aesthetic was embraced and interpreted through the exoticism of French Polynesia, and was now revealed to a European audience.

One of the most memorable creations was a suite of jewellery by Boucheron which drew direct inspiration from African culture – the bracelet was fashioned in malachite, red glass, ivory and gold with a marked geometric form. Yellow gold and ivory are seen in traditional African jewels, while the strong contrasting colours and structure acknowledged the Art Moderne movement. The piece is unusual given the omission of facetted stones of any kind, instead it utilises solid links of contrasting colour to dramatic effect. A necklace was also produced, made up of contrasting red and green panels. But the bracelet was most clearly aligned with the arts of Africa, and through its configuration, colour and materials it was an unequivocal early 20th century reinterpretation of the continent’s tribal jewels.

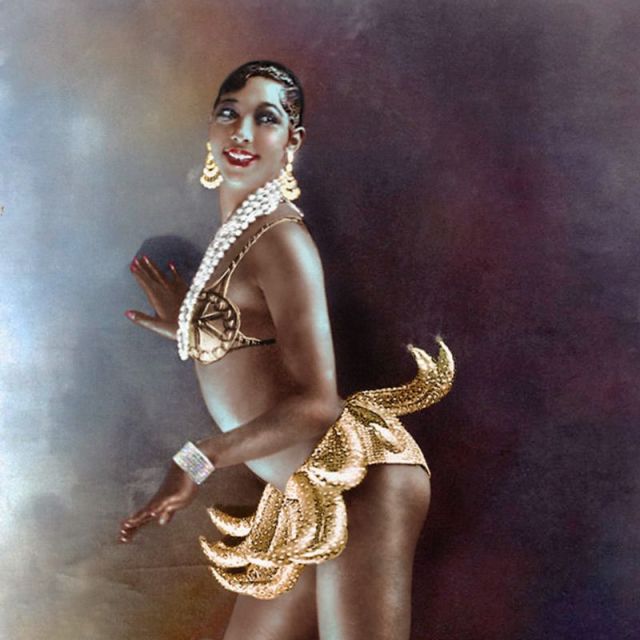

The exhibition helped to promote the desire for simplified jewels, which in essence led to the move towards traditional crafts, which was particularly favoured in the Depressions era of the 1930s. Beads of amber and ivory complemented with multiple bangles of exotic polished woods, lacquer and ivory became highly fashionable accessories for the fashionistas of the period. Cecil Beaton photographed Nancy Cunard, the shipping heiress, embracing the trend. Her arms were bedecked with multiple African bangles, she was known as a devotee of the new ‘barbaric look’ and she collected both African art and artifacts. The look was also popularised by Josephine Baker, who performed an outlandish and erotic ‘danse sauvage’ and captivated audiences with her daring skirt of stringed bananas.

By contrast, Cartier had earlier in 1919 created a series of elaborate jewels titled Soudanais – bangles of torque design resembling both gold and silver African examples from Nubia as well as those from ancient Europe. They were fashioned in ivory with elaborate inlays and were influenced by Sudanese designs with their incised ring and dot decoration, diamonds and pearl embellished the jewels and coral was used at the terminals. These elaborate and luxurious pieces were of course far removed from the traditional African jewels from which they were derived, although the use of ivory created the sense of exoticism and the link to Africa. The bangle is possibly the form from the fashion of this era which has had the most enduring influence, be it in simple lacquer or decorated with diamonds.

The African aesthetic continues to hold its sway in the output of contemporary jewellers. Boucheron replicated the important bracelet they created for the 1931 Exposition as part of their 2018 Nature Triomphante collection in the form of the ‘Graphique’ cuff’. In their reimagined bracelet, although the early and later designs are identical, the materials are very different. Only malachite is retained, with red glass and ivory replaced by onyx, black lacquer and diamonds, and it’s mounted in white rather than yellow gold. The bracelet displays its Art Deco roots; however, the use of diamonds places the piece firmly away from its original design source. Tiffany & Co have turned to Nancy Cunard with their black, ivory and red lacquer and Japanese hardwood bangles and the striking bone cuff created by Elsa Peretti.